You can listen to the Deep Dive here

On a podcast in 2022, Ted Gioia, who wrote 12 books on Music, aptly captured music's essence in our lives:

“I've always tried to dig into why music is important, Why is it a key part of our society? Why do people like certain songs? And a few years back, I wrote a history of the love song, but I was looking into these hormones that are released in the body when we sing, and a very interesting thing is they make you more trustworthy of the people that are around you. That's why countries have national anthems. That's why labor unions have their songs. That's why sports teams have their songs. And it's also why when you go out on a date, you go on a date to a music club or dancing…the music brings you together with the people you're around.

…if you don't understand these things, you don't realize how essential and closely connected the musical culture is to other things. I often tell people, many of us are here today because of a song. If our parents hadn't heard a song, we might not be here today.”

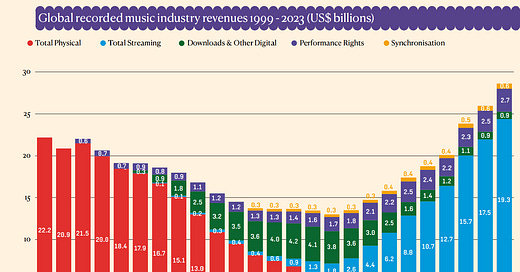

While music clearly leaves an indelible effect on most of our lives, it has not been easy for capitalism to capture the value created by music. In 1999, global recorded music industry generated $22.2 Billion revenue; it took another two decades for the industry to surpass that number! Even though revenue in nominal dollars finally exceeded the former peak revenue in 1999 by the end of 2021, on an inflation-adjusted per capita basis consumers today spend almost half of what they used to spend on recorded music in 1999.

One can, of course, argue that perhaps we were spending too much on music back then. There was likely little consumer surplus left in late 90s in the music industry as consumers had no option but to spend their hard earned money to buy the entire album of their favorite musicians even if they were only interested in listening to one particular song! This was likely a good deal for the superfans, but certainly quite a suboptimal deal for supermajority of casual fans.

Then when Napster came along, pervasive music piracy threatened the very core of recorded music industry since anyone could download almost any music they want for free. It is not a coincidence that recorded music industry revenue temporarily peaked at the very year Napster was founded in 1999. Record labels such as Universal Music, Sony, and Warner, who owned vast majority of the rights to recorded music at that time, were potentially looking at terminally declining business. Thankfully, Steve Jobs came to rescue the recorded music industry through the launch of iTunes in 2001.

As the era of illegal file-sharing threatened to tear down traditional structures in music industry, this new marketplace provided a lifeline, offering listeners a legitimate path to build their own libraries—one song at a time. Suddenly, music could follow fans wherever they went, slipping into pockets and playlists, shaping itself to fit their moods and moments.

However, that wasn’t enough; as you can imagine, it is very difficult to compete against free. Recorded music revenue continued its decline for years after the launch of iTunes.

While music labels began to unbundle their music offerings by selling songs individually, the simple price tag of a download still failed to capture a tune’s enduring charm. Everything cost the same 99 cents, be it Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” that you may listen again and again for decades, or some forgettable music that you may only listen once or twice. That was clearly suboptimal for both the listener, and the artist.

This paved the way for a new chapter: the era where artists are compensated with each play, where playlists evolve with listeners, and where the world’s music finds a home in the cloud. Services like Spotify reshaped the value of music, making the price of access more appealing than the pursuit of piracy, and transforming digital streams from a niche revenue stream into the industry’s main lifeline. While even ten years ago, streaming was just ~10% of global recorded industry’s revenue, it is now two-third of the overall revenue.

Music streaming value chain, however, reminds me of credit card transaction value chain. It can be deceptively simple for the consumer; you just pay a fixed subscription to access almost the entire catalog of available music in the world. However, the music streaming value chain can be dizzyingly complex. Before we get to more granular discussion on Universal Music Group, let me dissect the music value chain first.

After the discussion on music value chain, the rest of the Deep Dive is outlined below:

UMG Business Overview: I have covered an in-depth overview of UMG, and the economics of the business.

Bull/Bear Debates: I have focused on four key debates among bulls and bears: a) The Economics Between Artists and Labels, b) The rising multiple and valuation for catalog music acquisitions, c) The Economics Between DSPs and Labels, and d) Is AI tailwind or headwind for Labels?

Capital Allocation and Management Incentives: UMG’s capital allocation policy as well as how the management is incentivized is scrutinized in this section.

Model Assumptions and Valuation: Model/implied expectations in the current stock price are analyzed here.

Final Words: Concluding remarks on UMG, and disclosure of my overall portfolio.